I've always loved the Fourth of July. From the parties my parents hosted when I was a kid, to fireworks, to Boston Pops concerts, the whole thing is thrilling and makes me very proud. In fact, when Christy and I returned from England ten years ago-- guess which date we chose for our triumphant return? Yep-- the Fourth of July. And we celebrated with a little Fourth of July Rangers baseball. I was so exhausted and tired I watched the fireworks with sunglasses on! I think I'll try to squeeze in an Arlington trip this Sunday night with James and Miles!

I've always loved the Fourth of July. From the parties my parents hosted when I was a kid, to fireworks, to Boston Pops concerts, the whole thing is thrilling and makes me very proud. In fact, when Christy and I returned from England ten years ago-- guess which date we chose for our triumphant return? Yep-- the Fourth of July. And we celebrated with a little Fourth of July Rangers baseball. I was so exhausted and tired I watched the fireworks with sunglasses on! I think I'll try to squeeze in an Arlington trip this Sunday night with James and Miles!Thinking about the Fourth of July, I always consider some of the Americans who lived out the greatness our country aspires to. Obviously Lincoln, King, Douglass, Washington, Jefferson, and others come to mind, but this year I wanted to consider the life of someone not so easily recognized, and I settled on Arthur Ashe. I was a child when Ashe won his grand slam victories, and too young to understand the struggles he represented and endured as an African-American growing up in the South. When Ashe died in 1993, I was moved by the many moving tributes to his life-- not as a successful athlete or businessman, but as an American. A symbol to aspire to. One of the most important, wonderful, inspiring books I ever read was Ashe's autobiography, fittingly called Days of Grace. I commend it to you if you have not read it.

Several years ago, Mom gave me a ton of books for my library, one of which I treasure above the others: The Book of Eulogies by Phyllis Theroux. It's exactly what the title implies. I'd like to share with you Arthur Ashe's eulogy, written as an editorial in the New York Times. I'll also include introductory comments about Mr. Ashe written by Theroux. Her comments will be written in italics.

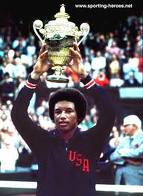

Arthur Ashe, from Richmond, Virginia, was the first male African-American tennis player to reach any degree of prominence in the sport. He received a tennis scholarship from UCLA in 1962; he was the first black U.S. Open champion; in 1970, he won the Australian Open, but was denied a visa to the South African Open on racial grounds. Ashe went before the United Nations to protest the policy. In 1973, we was admitted to South Africa to play, and in 1975 he won the title at Wimbledon. After an intravenous blood transfusion, Ashe was found to have become HIV-positive, which resulted in his death. He was the first black Virginian to lie in state in the governor's mansion in Richmond.

Arthur Robert Ashe (1943-1993)

The rise of Arthur Ashe in tennis, crowned by his Wimbledon victory in 1975, took on the stature of a fable. He was a black man in a sport that seemed a metaphor for racism-- a sport played by white people in white clothes in white country clubs-- and for a time he was the best there was. He was also a rare champion who believed that personal success imposes broad responsibilities to humanity.

Mr. Ashe's life was linked to two of the great scourges of his day: racism and AIDS, the disease that led to his death last weekend. He confronted them head-on-- driven, until the end, by the unselfish and unswerving conviction that he was duty-bound to ease the lives of others who were similarly afflicted.

In 1970, Mr. Ashe began a public campaign against apartheid, seeking a visa to play in the South African Open. Three years later he won that fight and became the first black man ever to reach the final at the open. His appearance inspired young South African blacks, among them the writer and former tennis player Mark Mathabane...

Mr. Ashe took his crusade to America's inner cities as well, where he established tennis clinics and preached tennis discipline and provided hope to the young people who most needed it.

He contracted AIDS through a blood transfusion of tainted blood during heart-bypass surgery a decade ago. He learned of his infection in 1988, but did not disclose it until last April, after USA Today told him it planned to publish an article about his illness. After his public admission, Mr. Ashe campaigned vigorously on behalf of AIDS sufferers and started a foundation to combat the disease.

Mr. Ashe did not waste his fame; he used it to leave a mark on the social canvas of his time. For this he remains a model champion.

Mr. Ashe's life was linked to two of the great scourges of his day: racism and AIDS, the disease that led to his death last weekend. He confronted them head-on-- driven, until the end, by the unselfish and unswerving conviction that he was duty-bound to ease the lives of others who were similarly afflicted.

In 1970, Mr. Ashe began a public campaign against apartheid, seeking a visa to play in the South African Open. Three years later he won that fight and became the first black man ever to reach the final at the open. His appearance inspired young South African blacks, among them the writer and former tennis player Mark Mathabane...

Mr. Ashe took his crusade to America's inner cities as well, where he established tennis clinics and preached tennis discipline and provided hope to the young people who most needed it.

He contracted AIDS through a blood transfusion of tainted blood during heart-bypass surgery a decade ago. He learned of his infection in 1988, but did not disclose it until last April, after USA Today told him it planned to publish an article about his illness. After his public admission, Mr. Ashe campaigned vigorously on behalf of AIDS sufferers and started a foundation to combat the disease.

Mr. Ashe did not waste his fame; he used it to leave a mark on the social canvas of his time. For this he remains a model champion.

We'll celebrate the Fourth this Sunday in worship, singing traditional hymns, praying for our nation, its leaders, its civil and military personnel, etc. We'll also celebrate Communion with a special Great Thanksgiving written for the occasion. For those unable to be with us: be careful and have fun. Part of the Fourth July festivities I particularly recommend: check out Avalon, a wonderful film by Barry Levinson, who directed other films such as Good Morning, Vietnam and Rain Man. Avalon is Levinson's semi-autobiographical story of his family's coming to America, beginning with a grandfather in 1914. One of the most beautifully filmed movies ever, filled with great stories and themes. The Fourth of July is a recurring date in the film. Check it out.

Comments